As previously mentioned, on June 10, 2025, the quiet city of Graz, Austria, joined a grim global fraternity when a 21-year-old former student, identified as Arthur A. or Artur A., walked into his old high school and killed ten people before turning the gun on himself. Armed with a Glock 19 pistol and a sawed-off shotgun, he murdered nine students and one teacher, injured eleven more, and shattered any illusions that mass school shootings were a uniquely American disease.

The shooter had legally acquired both firearms just weeks before the attack, despite having recently failed a psychological screening to join the Austrian military. Austria, a country with historically tight firearm regulations, still allows civilians to obtain handguns and long guns with the proper permit, which requires passing a psychological evaluation. Somehow, the young man, considered too mentally unfit for the armed forces, had no issue passing the test needed for a gun license. A little America had crept into Austria’s laws. And as we’ve seen in the U.S., once the legal door opens, it’s almost always too late to close it.

The detail about him applying to the army is hardly surprising. Many school shooters have entertained or pursued military service. To them, the line between fantasy and reality is already blurred. They don’t distinguish between shooting “the enemy” on a battlefield and murdering children in a classroom. They want the validation of the uniform and the lethality that comes with it. When that route is denied, they often take matters into their own hands.

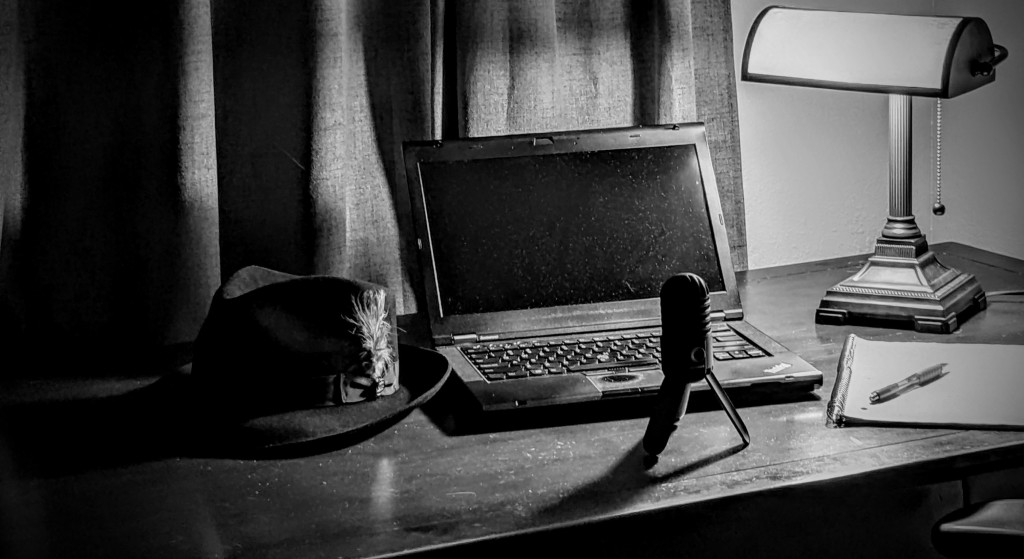

This one did just that. Before launching his seven-minute rampage, he entered a bathroom at BORG Dreierschützengasse high school, pulled on combat boots and black military-style pants, strapped on a weapon belt with a hunting knife, slid on shooting glasses, and donned a headset. He turned his toilet stall into a dressing room for war, a twisted nod to every over-stylized action movie he probably ever watched. He photographed himself crouched on the toilet and posted the image on social media, moments before unleashing hell. He had already posted photos of the weapons to Tumblr, calling them an early birthday present. He thought this was his moment.

The shooter was deeply obsessed with first-person shooter (FPS) games like Call of Duty and Valorant. Police described him as a loner whose only real social interactions occurred online with fellow gamers. He was an “obsessive” player, one who had retreated almost entirely into virtual combat. But let’s be clear, these games are not gruesome gore-fests like DOOM, nor do they feature any sort of narrative glorification of real-world massacres. They’re competitive, stylized, and, when taken in moderation, harmless.

Video games don’t make school shooters. There is no causal line from console to crime scene. Decades of studies confirm this, no matter how loudly former crusaders like Jack Thompson insist otherwise. But the genre does seem to attract the unstable. Something about the fantasy of power, control, and carnage resonates with those already on the edge. Games don’t create these people, but they do provide them with a sandbox to fantasize in.

This shooter didn’t just retreat into games. He immersed himself in the mythology of school shootings, particularly Columbine. He reportedly used a photo of one of the Columbine gunmen as a profile image under his gaming alias. His social media posts referenced that massacre, including one using the infamous “monsters” quote. This wasn’t just a casual curiosity, it was an obsession. Like many others in the columbiner subculture, he sympathized with the perpetrators, not the victims. Columbiners are usually young, isolated, mentally unstable, and romanticize school shootings, often framing them as righteous revenge or misunderstood acts of rebellion.

As I said in my initial post about the shooting, “The Columbine Effect” is most likely the motive behind the shooting. And yet, we still don’t know how far back this obsession goes. Did he grow fascinated with the shooters before he felt bullied? Or did the bullying drive him into that world? That question haunts nearly every case like this. And it matters because it flips the narrative. Maybe he wasn’t a victim who snapped, maybe he was a self-made disciple of violence who found validation in dark corners of the internet long before anyone noticed.

The answers won’t bring back the dead. But the questions remain, as they always do.

(Sources)

- Austrian school shooter an introverted fan of online shooting games, say police

- Graz gunman was first-person shooter games obsessive, police say

- Austrian police describe shooter as introvert who avoided outside world

- Austrian shooter posted online just before school massacre: Reports

- Austria school shooter posted twisted photo of himself minutes before massacre

Leave a comment